In hard-hit fishing communities, scientists engage fishers in conserving sea turtles

Beneath an open boat, two sea turtles glide easily in the clear, shallow saltwater. The young pair have ventured into a pound net used to catch flounder on the coast of North Carolina.

Kayla Burgher, a PhD candidate in the Senko Lab at Arizona State University, leans over the bow to haul in netting with help from Jasmine Abe, an ASU graduate student, also in the Senko Lab. A jumble of juvenile fish — jacks, croakers, flounder — squirm in the net as they are pulled to the surface with the green sea turtles.

Burgher uses a gloved hand to pluck one turtle from the net, then another. They have startling eyes, streamlined shells and powerful, paddle-like arms. One slaps at Burgher’s wrist as she gently places the scrambling turtle on the deck. Soon it will be released.

Sea turtles around the world are threatened with extinction. Despite signs of recovery, current population numbers remain a small fraction of the total that once existed. Fishing gear that entangles turtles unintentionally remains a primary threat, along with climate change, pollution, habitat loss and emerging diseases.

Recovery plans under the Endangered Species Act have imposed severe limits on commercial fishing in coastal North Carolina and other areas that are havens for green sea turtles, loggerheads and Kemp’s ridley sea turtles.

“It shut down the gillnetting here and there was a lot of people dependent on that,” says Eddie Willis, a fourth-generation commercial fisherman born and raised on Harkers Island, North Carolina. “It put a lot of people out of work. A lot of people.”

That has stirred anger and distrust of conservationists and scientists among people in fishing communities. “All they’ve heard is they are bad because they are killing sea turtles,” says Jesse Senko, an assistant professor in the School of Ocean Futures at ASU and leader of the Senko Lab. His team is studying ways to make fishing gear less harmful to sea turtles, sharks and other threatened species and thereby help sustain people who fish for a living.

In one series of controlled experiments in Mexico’s Sea of Cortez, Senko and colleagues showed that illuminating gillnets with green LED lights could reduce the capture of turtles and other off-target species by 63% while helping fishers save time retrieving and disentangling nets — all without interfering with the harvest and value of targeted fish… Full article

§

The promise of early detection

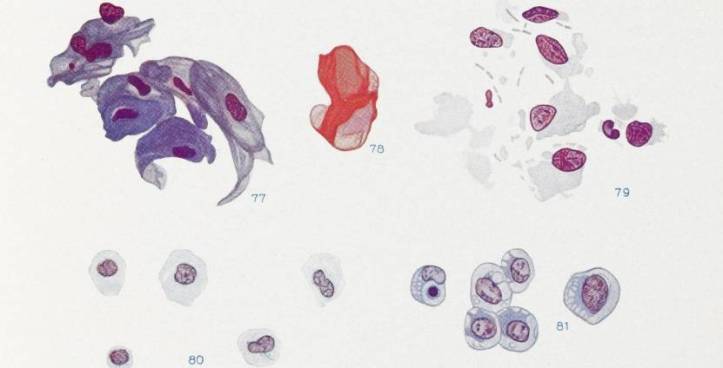

Nearly a century ago, a Greek immigrant physician in New York City began refining microscopy techniques for examining cells gently scraped from the female reproductive tract. The results were profound. George Papanicolaou’s Pap smear test gave the world a minimally invasive means to screen healthy women to reveal abnormally growing cervical cells that could be removed before any turned cancerous. And with it came the realization that cancer truly might be defeated by early detection.

Decades later, the promise of early detection remains largely unfulfilled for other cancers. But perhaps not for much longer. Powerful technologies are blooming and opening many paths forward. Progress in understanding the genes and cell signals that drive cancer has become so rapid that significant discoveries are now rolling out almost every week.

“As fast as we are making progress, ultimately we want to save more lives. And the fact that we can’t do it right now is frustrating to me,” said Brian Druker, M.D., director of the OHSU Knight Cancer Institute, speaking at the inaugural Early Detection of Cancer Conference in June.

The meeting brought many of the world’s leading scientists in the field of cancer early detection to Portland for the first of a series of international conferences planned by Cancer Research UK and the OHSU Knight Cancer Institute. The two organizations formed a collaboration last year aiming to accelerate progress in early detection research.

“Research in early cancer detection remains a relatively immature field,” said Sir Harpal Kumar, chief executive officer of Cancer Research UK. Most cancer investigators “are pursuing other avenues where funding is more certain and the rewards potentially greater within a shorter time frame,” he said. “Well, it’s time to change that.”

The promise – and the challenge – of early detection are well illustrated by the status of pancreatic cancer. Fewer than one in ten cases in the U.S. are diagnosed at the local stage. And the relative survival rate, around 6 percent at five years, is by far the worst among major cancers.

But studies of the path of gene alterations in pancreatic cancer suggest that there is a window of opportunity for detection before it spreads and becomes deadly. A much-cited study in the journal Nature estimated that it takes nearly 12 years, on average, for cancer-initiating gene changes to drive the formation of a tumor, and a further six or seven years for the tumor to develop the ability to spread via metastasis.

Cancers of the cervix and colon have been the most amenable to early detection because the tissues are accessible to sample for abnormally growing cells, which are relatively easy to identify and remove before they give rise to cancer. And the window of opportunity to do so lasts many years. The pancreas and other internal organs aren’t so easily accessed for sampling.

But rapidly advancing technologies are making it possible to glean significant information from the cells, fragments of DNA and other particles that tumors and abnormally growing tissues release into the bloodstream. Exosomes, for example, which are membrane enclosed particles secreted by cells, contain a trove of material from tumors: metabolites, amino acids, and DNA in relatively large, double-stranded fragments. Their existence was unknown until the 1980s. Now it may soon be possible to sequence the entire genome of a hidden tumor from the DNA fragments encapsulated in exosomes… Full article

§

MRI innovation for the first time reveals cells’ energy activity in organs and tissues

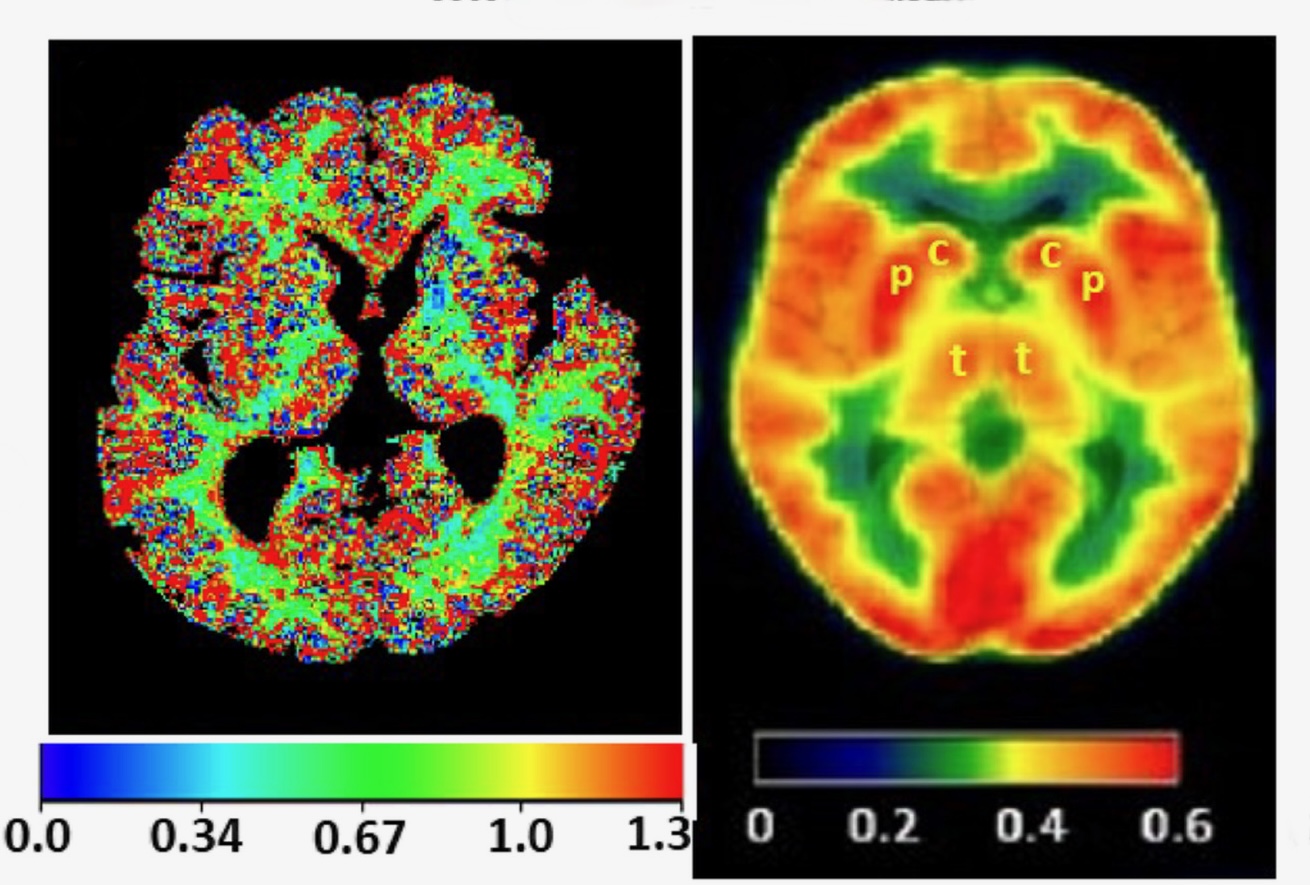

To survive, every cell in the body puts enormous energy into sustaining the right balance of water and essential electrolytes. Researchers at Oregon Health & Science University have developed a way to use magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI, to map this activity in fine detail in the human brain and other organs.

The innovation — called metabolic activity diffusion imaging, or MADI — is opening up new possibilities for detecting cancers and revealing if a tumor is responding to treatment. “MADI is a new way to make images of metabolic activity within organs and tissues at high spatial resolution, and it’s totally noninvasive,” said inventor Charles Springer, Ph.D. “In principle, this method could apply to almost any pathology.” Full article

§

The Billionaires’ Science Club

It was an entirely new and untested direction in cancer research. Realistically, it was not likely to succeed. You didn’t need a Ph.D. in biology to know that. But Wayne Kingsley, chairman of the Portland Spirit tour boat company, was intrigued by the story he was hearing from Dr. Walter Urba, a medical oncologist and cancer researcher in Portland, Oregon. Urba was caring for a friend of Kingsley’s with colon cancer, and Kingsley’s curiosity inevitably led to hallway conversations with Urba about his research.

“Rarely in your life do you get a chance to get involved in something like this,” says Kingsley, who with his wife Joan donated a few thousand dollars to the project. “It looked like it had potential. I liked the researchers involved. I thought, what the hay? Maybe these guys will be successful. It would be a win for Portland.”

Scientists led by Andy Weinberg on Urba’s team at Providence Health & Services had found a potential way to tweak a person’s native immune system to mount a highly targeted attack on tumors. The key was a protein called OX40. The researchers used antibodies to target OX40 and found that in laboratory mice, the treatment shrank a variety of tumor types, including breast, colon and kidney cancers.

To take the work to the next step — preliminary testing in human subjects — the team figured they’d need to raise at least $1.5 million. And that stood in the way like a forbidding mountain. It is almost impossible to get funding for that sort of research from the federal government. Out of sheer necessity, Urba and colleagues resorted to a Kickstarter-style campaign to raise the money from a crowd of private donors such as Kingsley.

Since 1993 federal funding for biomedical research has fallen by more than 22% at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), after accounting for inflation. Budget cuts are also shrinking the National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy, which support basic science, technology and engineering.

And everywhere, it seems, private donors wielding large checkbooks are playing an increasingly important role in the funding — and direction — of scientific research. For all the good such gifts are likely to do, the rising profile of philanthropists is troubling to some scientists and university leaders. Critics worry the trend could turn science into a popularity contest, with billionaires’ pet projects drawing money away from deserving but unsexy scientific fields, and from capable but lesser-known universities. Private philanthropy is unlikely to make up for what’s being lost in federal funding, and some fear that the attention-getting gifts of private billionaires will undermine political support for federal science agencies… Full article

§

Why big dinosaurs steered clear of the tropics

For more than 30 million years after dinosaurs first appeared, they remained inexplicably rare near the equator, where only a few small-bodied meat-eating dinosaurs eked out a living. The age-long absence of big plant-eaters at low latitudes is one of the great, unanswered questions about the rise of the dinosaurs.

And now the mystery has a solution, according to an international team of scientists who pieced together a remarkably detailed picture of the climate and ecology more than 200 million years ago at Ghost Ranch in northern New Mexico, a site rich with fossils from the Late Triassic Period.

The new findings show that the tropical climate swung wildly with extremes of drought and intense heat. Wildfires swept the landscape during arid regimes and continually reshaped the vegetation available for plant-eating animals.

“Our data suggest it was not a fun place,” says study co-author Randall Irmis, curator of paleontology at the Natural History Museum of Utah and assistant professor at the University of Utah. “It was a time of climate extremes that went back and forth unpredictably and large, warm-blooded dinosaurian herbivores weren’t able to exist nearer to the equator – there was not enough dependable plant food.”

The study, led by geochemist Jessica Whiteside, lecturer at the University of Southampton, is the first to provide a detailed look at the climate and ecology during the emergence of the dinosaurs. The results are important, also, for understanding human-caused climate change. Atmospheric carbon dioxide levels during the Late Triassic were four to six times current levels. “If we continue along our present course, similar conditions in a high-CO2 world may develop, and suppress low-latitude ecosystems,” Irmis says… Full article

§

Biochemistry researchers bring online gamers into the fold

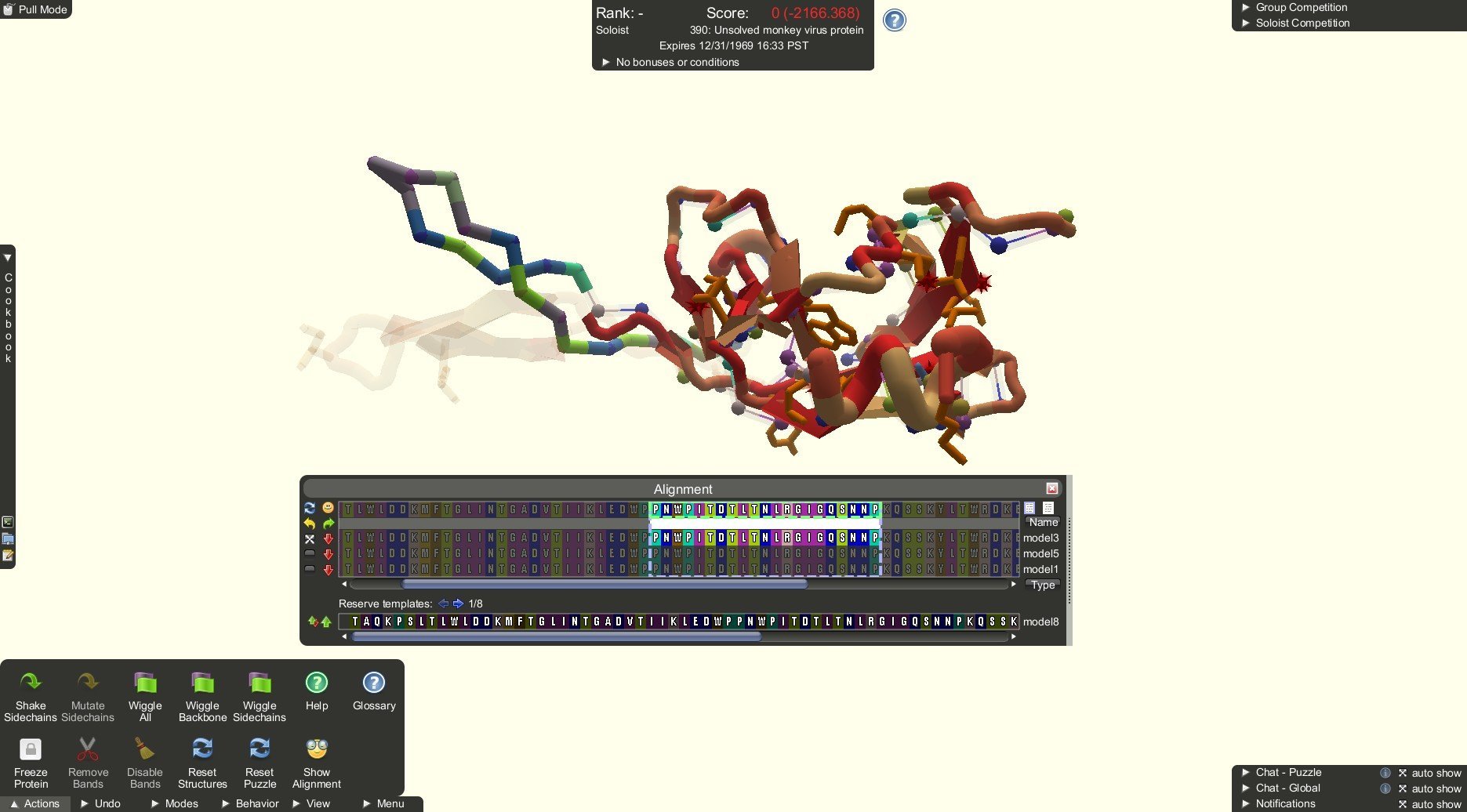

Scientists were stumped. For more than a decade, biochemists could not fully decipher the structure of a key protein, called a protease, that retroviruses such as HIV need to multiply. Knowing it would be a key step toward developing better anti-viral drugs.

So University of Washington scientists unleashed an avid group of online gamers. Within three furious weeks of play, pitting teams of non-scientists against each other, the gamers delivered the first accurate model of a retroviral protease.

There are many examples of citizen science, but most involve non-scientists helping out with drudgery, such as submitting data on animal sightings or running a distributed computing program on a home computer. Foldit players are providing answers beyond the capabilities of experts in the field. Full article

§

A citizen scientist coordinates global whale shark monitoring

In the distant underwater murk, the spots appear first, moving in unison like a school of fish. Coming closer, the illusion gives way. A shark the size of a city bus emerges, speckled and crosshatched like a checkerboard from head to tail, cruising fast and effortlessly through the warm sea.

“It’s an amazing pleasure to swim with them,” says Jason Holmberg, who met his first whale shark while scuba diving in the Red Sea in 2002. The giants — reaching lengths greater than 60 feet — use their cavernous mouths to suck up tiny plankton. They approach divers with curiosity. “Its eyes will track you; you can look at it, and it will look back at you,” he says. “It’s like contact with alien life.”

“It’s an amazing pleasure to swim with them,” says Jason Holmberg, who met his first whale shark while scuba diving in the Red Sea in 2002. The giants — reaching lengths greater than 60 feet — use their cavernous mouths to suck up tiny plankton. They approach divers with curiosity. “Its eyes will track you; you can look at it, and it will look back at you,” he says. “It’s like contact with alien life.”

Holmberg, 33, is a Portland-based software technical writer with a graduate degree in Arabic studies. From a bedroom office in a small house near Alberta Street that he shares with his wife, Melissa, and an Egyptian street dog named Hilmy, he coordinates a global whale shark monitoring project that is delivering a wealth of information about the mysterious species that lives half a world away. Full article

§

Why do people enjoy mouth-torching chile peppers?

What happens after you eat chile peppers reads like a list of drug side effects: burning pain, sweating, teary eyes and panic followed by lingering numbness. The plant makes its mouth-torching ingredients, called capsaicinoids, to stop animals from munching its fruit. Perhaps strange, then, how gardeners and cooks have avidly embraced the chile for more than 6,000 years. University of Washington scientists now propose an explanation: spiciness evolved as a chemical defense against microbial attacks. And people might have developed a taste for the powerful chile to take advantage of its anti-microbial powers. “That may not have been an accident,” said UW biologist Joshua Tewksbury, lead author of the study. “Eating chiles might have been very beneficial.” Full article

§

Monkeys with six parents push the limits of embryonic stem cells

The chimera of Greek mythology had a goat’s body, a lion’s head and a serpent’s tail. Using cloning tools, Oregon researchers have created chimeras of a sort: monkeys grown from a mix of cells taken from as many as six monkey embryos. The knowledge gleaned may prove useful for understanding human fertility, embryo development and the use of stem cells to treat diseases… Full article

§

What’s sex got to do with it? A lab worm reveals all

Why we bother with sex may seem obvious. “Behold, it was very good,” the Bible’s book of Genesis points out after man and woman fruitfully multiply. But evolutionary biologists have scratched their heads about sexual reproduction for decades because it’s far more efficient for living things to reproduce solo. Experiments with a millimeter-long worm are providing answers…Full article

§

How Corvallis, Ore., exceeds New York City: A view from theoretical physics

People in big cities do just about everything faster: walk and talk, create and invent, earn and spend, steal and murder. The speed increases prove surprisingly predictable. As a city’s population grows, its residents’ collective actions and behaviors seem to accelerate in a common pattern that can be described by the same mathematical formula. Scientists at Los Alamos National Laboratory and the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico, who worked out the math, draw some counterintuitive conclusions… Full article

§

Oregon site may hold signs of 1st Americans

Near the marshy edge of an ancient lake in south-central Oregon, wandering Stone Age hunters took shelter in a shallow cave at the foot of a basalt ridge. They camped briefly, leaving little evidence of their stay: a flaked-stone spear or arrow point, a few shards suggesting tool-making or sharpening, a grinding stone, and several piles of excrement preserved in the dry cave floor. From these unintended time capsules, scientists say they’ve extracted DNA that is unquestionably human. Carbon dating suggests that people first occupied the caves 14,300 years ago – more than a thousand years before the rise of the Clovis hunters, long presumed to be the first Americans… Full article

§

Trees of Life: Lone oaks are islands of refuge for wildlife

In a landscape dominated by grass-seed fields and pastures, an aged oak tree’s spreading dome of gnarled branches commands attention. Generations of farmers have plowed carefully around the really big ones. Some have stood for more than 300 years, since native white oak trees and grasses covered half a million acres across Oregon’s Willamette Valley. Less than 2 percent of that oak savanna remains. But although the old oaks cover only a tiny fraction of the landscape, they still may be changing how the whole ecosystem functions, to the benefit of many other species, including people.

Large, old trees improve nutrients and water retention in soils. They provide places for livestock to seek shade, for wild animals to nest and feed, and for native plants to grow. They become islands of refuge that allow animals to move around a landscape. “Their influence on wildlife may be disproportionately large, relative to their actual physical footprint,” said researcher Craig DeMars… Full article

§

In alcohol study, voles are real party animals

Prairie voles, by their nature, stick with one mate for life and devotedly care for babies together. But given alcohol to drink, many become staggering drunkards prone to stepping out on their partners. Sound familiar? The overlap with human tendencies makes the mouse-like rodent an ideal model to study the social aspects of excessive drinking… Full article

§

What babies are teaching scientists about the human brain

Problems like this arise constantly in life: You hit the “print” command on your computer and nothing happens. To get anywhere, you have to figure out whether the printer is broken or you’re just doing something wrong, like forgetting to turn on the power. Babies, it turns out, possess reasoning skills that make them adept at solving this kind of problem… Full article

Problems like this arise constantly in life: You hit the “print” command on your computer and nothing happens. To get anywhere, you have to figure out whether the printer is broken or you’re just doing something wrong, like forgetting to turn on the power. Babies, it turns out, possess reasoning skills that make them adept at solving this kind of problem… Full article

§

Some diets protect aging brains, others accelerate harm

Human brains tend to shrink and become less nimble in old age, but healthier eating may slow the process. A study of older adults in Oregon identified mixtures of nutrients that seem to protect the brain, and other food ingredients that may worsen brain shrinkage and cognitive decline. Unlike previous studies, which have relied on questionnaires to estimate nutrient intake, the Oregon researchers directly measured levels in the blood. Rather than focus on single nutrients, the researchers analyzed combinations of nutrients and how they related to brain health… Full article

§

Why wine critics are mostly wrong about terroir

Wine aficionados love to talk about “gout de terroir,” the taste of the soil. But don’t be fooled next time you hear one muse about the “weathered Devonian slate” or quartz soil “minerality” detectable in the grape. They’ve stretched the meaning of terroir to the point of silliness. Landforms, soils, climate and other local conditions shape the character of wine, but not in the oversimplified way wine writers would have it. Minerals absorbed from vineyard soils, for instance, do not make their way into the finished wine to give it a local flavor… Full article

§